Industry Shakers You Might Not Have Heard Of: Paul R. Williams

One of the most amazing things about the industry we work in is that we have the power to change lives and shape the future. Sounds a little intense, but think about it: buildings drastically impact the everyday lives of all people. That new school your team is working on might mean kids getting to college or exploring interests they never would have otherwise. The medical center your company built could one day lead to the cure for a rare disease. In construction, there is endless opportunity to transform the world we occupy.

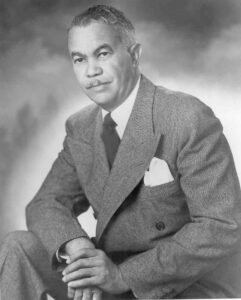

Paul R. Williams was an internationally renowned architect who worked primarily with celebrities to design beautiful homes for them.

Paul R. Williams was an internationally renowned architect who worked primarily with celebrities to design beautiful homes for them.

However, that doesn’t always mean that change is easy—or appreciated. This is especially true when you’re doing something for the first time. There’s no one else to look up to, no one else to give you a helping hand. More often than not, there are many more voices telling you that you’ll never be successful, and it can be many years before you see the fruits of your labor.

This was the road that Paul R. Williams, an internationally acclaimed architect, faced at the very beginning of his career. He came from humble beginnings, a foster child raised in downtown Los Angeles, and was discouraged by his own teacher from pursuing his passion for architecture despite showing an early talent for design. On top of this, he could not find any fellow Black architects to look to for guidance: he started his work in the early 1900s, in a time when people of color were not encouraged to pursue any interests that would require higher education or any kind of specialized training. But Williams knew that breaking barriers and setting new trends had to start somewhere and that the progress he made would someday pave the way for future architects just like him.

“Your Own Community Can’t Afford You”

Williams was raised in a relatively progressive ecosystem considering the era in which he spent the majority of his life, and as a result, he was able to explore his passion for design at an early age when he attended the Los Angeles School of Art and Design. However, it was at this very school that he was told by a teacher to give up trying to make a living out of architecture: the teacher said that the Black community wouldn’t be able to afford his services, and the white community wouldn’t hire him because of his skin color.

One of the gorgeous Southern California mansions that Williams designed.

One of the gorgeous Southern California mansions that Williams designed.

Such discouragement only motivated Williams more. While he would dabble in a range of concepts, including experimental structural and transport systems, Williams’ bread and butter came to be extravagantly beautiful homes for the wealthy—Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz of “I Love Lucy” fame commissioned him to design their Palm Springs abode, and even decades after Williams’ death, celebrities still compete to say they lived in one of his elegant mansions.

Although Williams rubbed shoulders with the likes of Cary Grant and Frank Sinatra thanks to his impeccable work, he never forgot about his roots. As he said himself: “Expensive homes are my business and social housing is my hobby.” Williams was involved in designing several affordable housing communities throughout the Southwest United States. One of the most notable projects was Berkley Square, a 40-acre Las Vegas development built in the 1940s that allowed for Black owners. This was a rarity at the time—most developments funded by the Federal Housing Authority did not let Black buyers apply to purchase a home. Williams also created the design for the integrated public housing development in Los Angeles, Pueblo Del Rio.

After World War II, Williams became very interested in prefabricated homes as well. He saw a great need for immediate, affordable housing, and he even wrote two books—The Small Home of Tomorrow and New Homes for Today—to offer insight into quickly and creatively building more of these types of instantly ready-to-go homes. He would end up partnering with Wallace Neff, an architect who happened to be his competition but who was also deeply invested in solving the housing shortage. Together they would submit dozens of proposals for prefabricated developments to be created in South America, Africa, the United States, and various Native American reservations within the U.S. Although none of their proposals were ultimately accepted, Williams played a huge role in popularizing the idea of prefabricated residential construction.

Necessity Is the Mother of Invention

A recreation of the upside-down drawing technique Williams taught himself.

A recreation of the upside-down drawing technique Williams taught himself.

Williams was as talented as he was passionate, and he discovered several ways to continue making a name for himself even when faced with massive obstacles. Williams was known for being an extremely skilled draftsman, to the point that he was even able to draw buildings completely upside-down. But this wasn’t just a clever trick Williams happened to have up his sleeve. He made himself develop this technique because it let him sit across rather than next to his white clients so that they felt more at ease. He would tour construction sites with his hands held gracefully behind his back, giving the air of royalty while also allowing his clients to choose whether or not to extend their hand first for a handshake.

Despite Williams’ career taking off like a rocket, he wasn’t able to live in many of the places that he designed homes for. Some Los Angeles neighborhoods even forbid him from spending the night. Nevertheless, he persevered because he believed “that for every home and every commercial building that he could not buy and that he could not live in, he was opening doors for the next generation," writes Karen Grigsby Bates.

The Legacy He Left Behind

The iconic Theme Building at the LAX Airport that Williams helped design.

The iconic Theme Building at the LAX Airport that Williams helped design.

Williams’ talent extended beyond residential work, of course, and he would go on to design other well-known Southern California landmarks like the Palm Springs Tennis Club and the Los Angeles Saks Fifth Avenue. He also earned a number of honors both during and after his life. He became the first Black member of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in 1923, and in 1957 he made history again when he became inducted into the AIA’s College of Fellows. He would then be posthumously recognized twice, once by USC for being a distinguished alumnus in 2004 and the second time by the AIA who honored him with the AIA Gold Medal in 2017, the organization’s highest honor given only to those whose “work has had a lasting influence on the theory and practice of architecture.”

While Williams died in 1980, his legacy continues in the buildings he left behind and the trails that he blazed for everyone who would come after him. We can't think of a better person from our industry's past that represents our core values so well: passion for his craft, innovation in overcoming systemic challenges, and caring for the communities so often ignored by too many people.

-1.png?width=112&height=112&name=image%20(4)-1.png)