Rebels of Construction—Bruce Goff

Bruce Goff (June 8, 1904-August 4, 1982) embodies the exact spirit of what this blog series is about. A true rebel and disruptor in every sense of the word. “Unconventional” doesn’t quite cut the art and architecture of Bruce’s career.

“There is no mystery force that made me want to be an architect. It was strictly chance. If my father had not apprenticed me when I was 12, I would never have done it on my own, although I did make drawings of buildings” -Bruce Goff

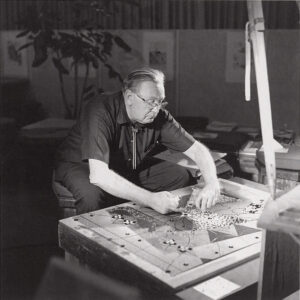

Bruce Goff often crafted the interior details of his homes himself. (Photo courtesy of papercitymag.com)

Bruce Goff often crafted the interior details of his homes himself. (Photo courtesy of papercitymag.com)This man, who spent his early childhood in small towns in Oklahoma in the early 1900s, had always marched to his own beat and lived life through his art that greatly impacts many today. Over 500 structures in the United States—mostly in Oklahoma and the mid-west—bear his eclectic style. Though thoroughly recognizable as unique, unless you studied his work, you wouldn’t be able to say, “Oh! That’s a Goff house!”

During his most productive years, Bruce’s name never became synonymous with “famous architect.” It’s a shame because even Bruce’s one-time mentor and lifelong friend, Frank Lloyd Wright, described Bruce as one of the only truly creative American architects.

Bruce Goff was born in Alton, Kansas on June 8, 1904. His father, Corliss, was a watch repairman and had his own shop in Alton. Life was rough - the Goffs were very poor. Bruce recalls always being interested in drawing, particularly castles and cathedrals. He never had drawing paper, though, as it was an expense the Goff’s couldn’t afford, so Bruce would draw on the back of all wrapping or wallpaper.

Corliss moved his family around when Bruce was young, seeking better opportunities to provide. When Bruce was two, they left Kansas for Oklahoma and lived in a series of small towns—Henrietta, Skiatook, and Hominy, where Bruce was introduced to the Native Americans living in Oklahoma. He was awe-struck with their use of color in an otherwise drab and dusty environment. He would continue to draw inspiration from this time in his life, incorporating bright colors and vivid patterns in his work.

Bruce designed the McGregor House, now on the National Register of Historic Places, when he was a teenager.

Bruce designed the McGregor House, now on the National Register of Historic Places, when he was a teenager.In 1915, Corliss gave up the watch repair business and moved the family to the bigger town of Tulsa, Oklahoma to sell grocery equipment. Bruce recalls a night one year later after moving to Tulsa when his father came home one evening quite tipsy and told Bruce to get ready, as they were going downtown. Once the pair got to downtown Tulsa, Corliss stopped a stranger on the street and asked which architectural firm was the most respected. The stranger told them it was Rush, Endacott and Rush. Corliss proceeded to march Bruce into the firm and demanded they teach Bruce how to be an architect. They agreed. So, at just 12 years old, Bruce began his apprenticeship. This was to be his only formal education in architecture.

While at Rush, Endacott and Rush, one of the fellow architects at the firm accused Bruce of copying the already well-known Frank Lloyd Wright’s work. Bruce had never heard of Frank Lloyd Wright but after the accusation, Bruce looked him up. He says, “When I first saw Mr. Wright’s work in 1916 or 1917, I was extremely impressed. In fact, I couldn’t eat, sleep or think of anything but Wright for three years.”

Bruce decided to write to Wright, addressing the envelope “Frank Lloyd Wright, Taliesin, Wisconsin.” The letter made it to Wright, who replied to Bruce by sending an original edition of his Wasmuth portfolio and a signed letter that said, “Happy to Know I have a friend in Tulsa, Oklahoma.” (papercitymag.com)

Bruce and Frank Lloyd Wright in 1949. (Photo courtesy of the Bruce Goff Collection, Ryerson and Burnham Archives, Art Institute of Chicago.)

Bruce and Frank Lloyd Wright in 1949. (Photo courtesy of the Bruce Goff Collection, Ryerson and Burnham Archives, Art Institute of Chicago.)Frank Lloyd Wright was not only a mentor to Bruce, but the two were lifelong friends. Frank asked Bruce multiple times to be his “right-hand man,” but Bruce declined every time. Also, when Bruce asked Frank if he should attend MIT, Frank discouraged him from getting any academic training as Bruce would “risk losing what made him Bruce Goff in the first place.”

There is evidence of Bruce’s earlier time at Rush, Endacott and Rush—while still attending high school, a few of his home designs were built in Tulsa and when he was just 22 years old, Bruce was awarded his very first commissioned work—the Boston Avenue Methodist-Episcopal Church in Tulsa.

Bruce’s most productive and artistic work period was from 1947 to 1955 when he was the chairman of the School of Architecture at the University of Oklahoma. He shifted the way the school taught to encourage creativity and imagination. According to the University of Oklahoma’s America School of Architecture, students “…were encouraged to develop responses to site, function and client rather than imitate historical forms or copy abstract art.” Philip B. Welch, one of Bruce’s former students, wrote, “He never told students what to do; he led them back to their own sense of self and let them work it out from within.”

Bruce moved his studio to the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Price Tower in Bartlesville, Oklahoma.

Bruce moved his studio to the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Price Tower in Bartlesville, Oklahoma.Not only was Bruce’s teaching and leading style controversial during his time at the university—he was chastised because he never forced his theories or style of design on his students. Bruce's lifestyle didn't match the school's expectations and he was accused of “endangering the morals of a minor.” Though you can’t find anything official, it is widely reported that he was essentially forced to resign from his position at the University. Those who knew him and have published articles on him do not mention any of this. He left the school in 1955. After leaving the university, Bruce moved to Bartlesville, Oklahoma, and opened a studio in the Price Tower, which was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright—Wright’s only skyscraper.

“I respected him because he was so unique artistically. But he was also logical mathematically. His houses were both innovative and pragmatic.” -Ted Seligson

Bruce’s Work

Bruce designed the Hopewell Baptist Church in Edmond, Oklahoma to resemble a teepee. It was built by the congregation of the church using old oil field pipes. (Photo courtesy of Hyperallergic.com)

Bruce designed the Hopewell Baptist Church in Edmond, Oklahoma to resemble a teepee. It was built by the congregation of the church using old oil field pipes. (Photo courtesy of Hyperallergic.com)As is common when people don’t understand something, we tend to make up labels. Bruce’s (un)style is now called “organic architecture.” It is nearly impossible, though, to nail down exactly what Bruce’s style was, as every structure was unique. Bruce designed specifically for those who lived in the homes, in the way they wanted to live. He was very aware of the spatial experience of the home at each level. At first look, he says each home added up to an “impressive whole,” yet, as you drew closer to the house, its details were apparent everywhere you looked.

He never followed the rules of architecture, design, or construction, and his homes were often called “abominations.” He played with light, movement, and shapes, often using found materials such as plastic sheeting and dollar-store ashtrays to capture the natural environment surrounding the house in hopes of eliciting feelings of calm and peace for its inhabitants.

One home he designed for a farmer in Minnesota was the first home to incorporate indoor/outdoor carpet on the roof. When asked why, Bruce replied, “I wanted the color and to try it.” Another home, the Jacob Harder House in Mountain Lake, Minnesota is covered in fish-scale shingles, which Bruce was told could never be done. Bruce was also one of the earliest designers to take broken pieces of marble that would otherwise be thrown away and make unique mosaic flooring out of them.

The Bavinger House

The Bavinger House was made of 200 tons of local rocks and anchored by a recycled oil field drill stem. It took the Bavingers—who built the house themselves—5 years to complete its construction.

The Bavinger House was made of 200 tons of local rocks and anchored by a recycled oil field drill stem. It took the Bavingers—who built the house themselves—5 years to complete its construction.One of Bruce’s most well-known homes was the Bavinger House, designed for Eugene and Nancy Bavinger, both art professors at the University of Oklahoma. The Bavingers did most of the construction themselves. The Bavinger House had no rooms—only flexible-use, fully carpeted pods suspended from the ceiling.

The Bavinger House had no rooms, only suspended pods.

The Bavinger House had no rooms, only suspended pods.In June 2011, the Bavinger House was leveled under mysterious circumstances. Eugene and Nancy’s son, Bob Bavinger is quoted in the June 29, 2011 edition of the Oklahoma Gazette newspaper, “It was the only solution that we had. We got back into a corner." (hyperallergic.com)

The Joe Price House

Shin’enKan, one of Bruce’s most renown homes was tragically destroyed by arson in 1996. It was located in Bartlesville, Oklahoma.

Shin’enKan, one of Bruce’s most renown homes was tragically destroyed by arson in 1996. It was located in Bartlesville, Oklahoma.Sadly, another one of Bruce’s most ambitious projects is also no longer standing. More recently referred to as Shin’enKan, Bruce originally designed the house in 1956 for friend Joe Price. Located in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, the Joe Price house was a home 25 years in the making with additions made in 1966 and 1974.

The home had many unique properties. Bruce glued five pounds of goose feathers to the ceiling of the main living room to diffuse light from a skylight. He designed a humidity pool inside the home to protect the delicate rice paper of Joe’s extensive Edo Japanese art collection. The master bedroom’s walls were made of Kentucky coal and turquoise glass culets from the Liberty Glass Plant in Sapulpa, Oklahoma.

Joe Price married and eventually, he and his wife moved to California, donating Shin’enKan to the University of Oklahoma. On December 26, 1996, the house caught fire by arson and burned for days. The case was never resolved.

“Mr. Goff was the most original, extraordinary person I have ever known in my life.” -Robert Morris

Bruce Goff died in August 1982. Unfortunately, because he was never recognized like many of his contemporaries, there hasn’t been much action in protecting his homes and buildings from vandalism and decay. For someone who fell into architecture by “accident,” as Bruce says, he was widely sought out by those familiar with his work and profoundly inspired his students and the generation of architectures after.

This post is part three of our series titled “Rebels of Construction.”

What Does it Mean to be a Rebel?

Rebels challenge conventional ways of thinking, defy rules, and rise up against those that tell them ‘no.’ Without Rebels, there would be no invention, innovation, or improvement in our society. Disrupting the status quo, a true Rebel charts a new course where all benefit. In the blog series, Rebels of Construction, Beck Technology celebrates the independent spirit of the Rebel.

-1.png?width=112&height=112&name=image%20(4)-1.png)