The History of Construction Safety Week

You’re probably used to that familiar email hitting your inbox by now, announcing the beginning of another year’s Construction Safety Week. It’s a great reminder to make sure your team is staying up-to-date with current safety standards, as well as ensuring that you’re maintaining a holistic view of safety. With increasing awareness of the importance that mental health plays in both our personal and professional lives, this year’s Construction Safety Week theme is focused on making sure people in the industry know that safety isn’t just limited to the job site.

What is Construction Safety Week?

What is Construction Safety Week?

But did you know that Construction Safety Week is actually a pretty new phenomenon in the world of building? It didn’t officially begin until 2014 when two other initiatives—Construction Industry Safety Initiative (CISI) and Incident and Injury Free (IIF) CEO Forum—came together to “inspire everyone in the industry to be leaders in safety.” It was then more officially branded and developed into a true annual campaign a few years after its origins, in 2018. Since then, Construction Safety Week has morphed into a movement that has its own website with a plethora of resources for industry professionals to utilize. There are daily topics in the form of 60-second videos; PowerPoint slides and playbooks; translated materials in Spanish and French, and even downloadable activities for employees to do at home with their families.

Now that you know a little bit more about the origins of Construction Safety Week, let’s take a step back and look at how safety standards and best practices have evolved over time, laying the groundwork for what we use today.

The Industrial Revolution Spurs Change

It wasn't until the turn of the 20th century that the U.S. government would issue federal requirements around construction safety measures.

It wasn't until the turn of the 20th century that the U.S. government would issue federal requirements around construction safety measures.In America, construction safety requirements as we now know them really did not exist until around the Industrial Revolution in the late nineteenth century. As society moved away from an agrarian lifestyle and toward a more urban, mass-produced one, dangerous working conditions abounded. Ridiculously long hours, unsanitary working environments, zero PPE or regulations—all of these became extremely commonplace, and construction was definitely not spared.

Massachusetts was the first state to pass any kind of law in regards to on-site safety. Passed in 1877, this new law now required job sites to mandate precautions such as proper fire exits and guards for shafts, gears, and belts. These are things we take for granted today, but at the time they were passed, they were considered groundbreaking. About a decade later, nine other states would follow in Massachussetts’ footsteps and pass their own regulations.

It wasn’t until the turn of the 20th century, however, that the U.S. government would issue federal requirements around construction safety measures. In 1912, the government formed the National Council for Industrial Safety—known simply as the National Safety Council today. This group was tasked with collecting incident/injury data and using it to help develop accident prevention initiatives. There had been no official record-keeping prior to the council’s formation. In just a year of their existence, they found that a total of at least 19,000-21,000 employees died from workplace-related injuries.

Joseph Strauss Innovates on Existing Standards

By the middle of the twentieth century, the fight for workers’ rights across all industries was in full swing, and more and more research was emerging that supported the idea of treating employees more like humans and less like cattle. It was becoming clear that neglecting the health and safety of employees could have severe consequences—not just for the individual, but for the company’s bottom line as well. At this point in time, safety standards were no longer groundbreaking revolutions but rather industry expectations.

Joseph Strauss, the chief engineer on the construction of the Golden Gate Bridge, was pivotal in establishing construction industry safety standards.

Joseph Strauss, the chief engineer on the construction of the Golden Gate Bridge, was pivotal in establishing construction industry safety standards.This was where Joseph Strauss came in. In 1933, Strauss had been selected as the chief engineer on a truly ambitious project: the Golden Gate Bridge. This project was considered especially challenging because it was going to be the first suspension bridge supported by a tower dug into the ocean. In addition to that, those who worked on the project would be immersed in harsh, often unpredictable weather and water conditions. As a result, those applying to join the crew of the Golden Gate project were considered reckless daredevils who would—at least based on the reputation of other bridge workers—be navigating a brutal environment with little to no precautions.

Existing data at that time supported this stereotype. The construction industry had come to find that for every million dollars spent on a project, one man would die. The Golden Gate bridge cost thirty-five million dollars. So Joseph Strauss was looking at a never-done-before project and an extremely high death count on his hands. He decided that he wasn’t going to lose that many men. In fact, he decided that he was going to try not to lose any if at all possible.

Strauss demanded the most up-to-date precautions on the Golden Gate project and even came up with a few of his own. He had a mesh safety net commissioned to be built under the floor of the bridge while they built the roadway structure. This innovation ultimately spared the lives of nineteen men who would come to be nicknamed the “Halfway to Hell Club.” Strauss also required his workers to wear hardhats and respirators to prevent lead-tainted fume inhalation, and he was so serious about these requirements that he would fire anyone who didn’t follow them. And that wasn’t all: workers had access to an on-site hospital, special hand and face creams to protect their skin from the harsh winds, and specific diets to follow so that they could fight dizziness during the tower and roadway construction.

Strauss did end up losing eleven men over the course of the four-year project. But a similar project, the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, saw twenty-eight fatalities. Strauss’s strict requirements proved to the world that safety gear and other preventative measures did save lives, and the steps that he took on the Golden Gate project would soon become the new industry standard.

Present Day Innovations

OSHA has plenty of printed safety materials you can use.

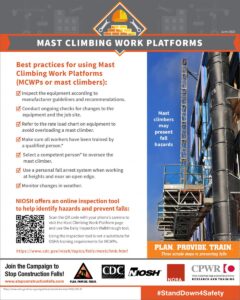

OSHA has plenty of printed safety materials you can use.Since those days of no regulation and lack of oversight, the Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA) was founded, as well as the National Occupational Research Agenda. Both of these organizations help contractors maintain existing safety standards while also continuing to perform research and publish data to innovate improvements upon those standards. As a result, some of these latest innovations include the use of drones, which can do a large majority of site surveying as well as monitor job sites to make sure everyone is adhering to safety guidelines. Hard hats have recently started to become outfitted with carbon monoxide sensors so that they can alert workers and give them a chance to get out in time. Finally, site sensors are also getting popular – they’re able to monitor and send alerts for things like noise level, volatile organic compounds, and temperature.

If you’d like to learn more or access some of the resources mentioned earlier, just go to www.constructionsafetyweek.com.

-1.png?width=112&height=112&name=image%20(4)-1.png)